Seating Arrangements – from Let Me Know When You’re Home: Stories of Female Friendship

by Sara Sherwood

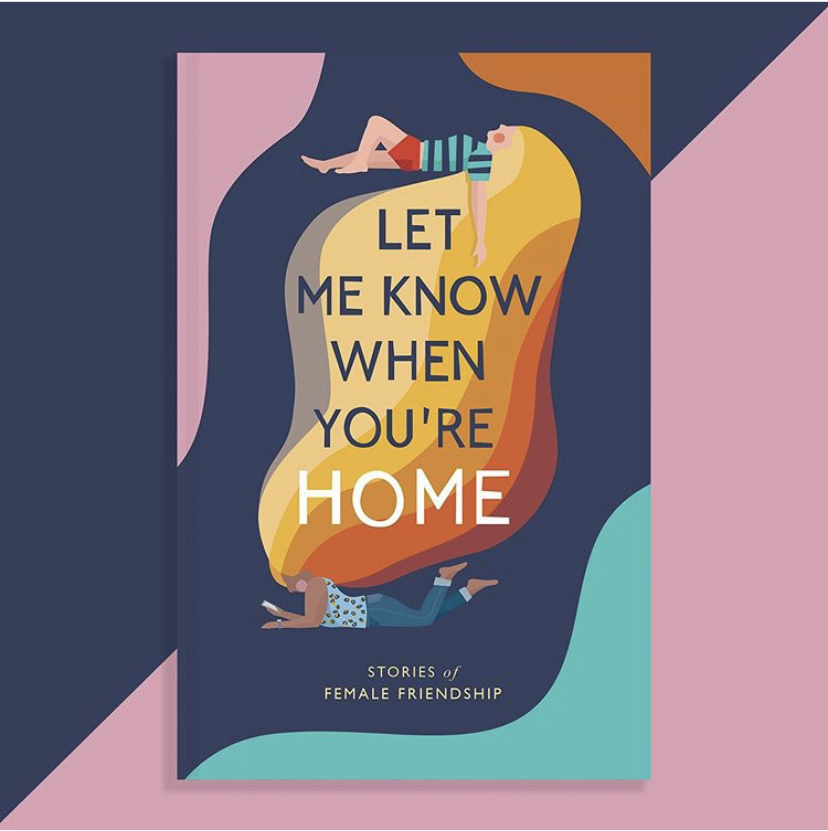

Over the years, we’ve loved seeing how our first collection, Let Me Know When You’re Home: Stories of Female Friendship, has been embraced by our community – passed between friends old and new, celebrating the special relationships between women.

If you haven’t yet read the collection, here’s a taster for you to try out. Sara Sherwood’s short story, Seating Arrangements, follows old friends at a dinner party and looks at how distances can form between even the closest of people.

“I’ve put Isobel next to Jules. They both work for charities; they’ll have loads to talk about. I’ve sat vegan Thom next to Nisha; she works for The Co-Op. I think that works, right? They’ll probably talk about… the co-operative movement?”

“Chartism? The Peterloo Massacre? Mike Leigh’s film? Maxine Peake?”

“No, something more modern.”

“The formation of the welfare state? The miners’ strike? The downfall of Thatcher?”

“You’re right. Thatcher. That’ll get their knickers wet.”

“Hate can be a powerful aphrodisiac. Hating the same people is how we became friends.”

“I suppose. He works in sustainability, so they can talk about… plastics? Blue Planet? Do you understand what he actually does? I’m too embarrassed to ask again.”

“No. He uses so much jargon that I just stop listening when he talks.”

“He does tend to drone. And your incredible skills at withstanding droning in mind, I’ve put you next to Thom. I’m on your other side and Jack is next to me.”

“Sounds good,” I say. Poppy has used her calligraphy pens to create individual place-cards for all the guests. I run my finger over the loops of your name. “Why don’t you swap me and Isobel? You’re the only one who likes her.” I reach my hand towards Isobel’s name card.

“No movement!” She adjusts the place card even though I didn’t touch it. “And I’m not subjecting you to that. You’ve met Jules, haven’t you? The one who came to the pub with Jack the other night and bored on about Paul Thomas Anderson films. I was like, yes, Jules, I too have seen The Grand Budapest Hotel.”

I could just tell Poppy. Tell her that my pillow still smells of you. That my tongue was in your cunt less than six hours ago. That when you made me cum with your fingers this afternoon, I bit your shoulder and my teeth marks were dented against your skin. That three weeks ago, when you were curled against my back, your snores fluttering against my neck, I told you that I loved you.

“That’s Wes Anderson. And yes, I have met Jules before.”

“Whatever. Still a man with a camera.”

“Have you ever noticed how Isobel says her parents worked really hard to send her to private school? And she once said she really admired Michael Gove?”

“Let’s not get into that again. What do you think of the table? Nice, right?”

“Yeah. You’ve got chairs. And plates, I’m assuming.”

“Yes, and cutlery.” Poppy turns to me. She takes a deep breath. “Do you think people will think I’m a twat because I’ve bought a house and I’m showing off with a dinner party?”

I shuffle my arm around Poppy’s shoulder.

“People won’t think you’re a twat unless you ask them to bring their own wine.”

Poppy is silent.

“You didn’t ask people to bring their own wine, did you?”

Poppy remains silent. I withdraw my arm.

“You could afford a house, but you couldn’t buy a couple bottles of wine?”

“Half a house. Half a deposit for a house.”

“You’re right. Famously, houses, compared to wine, are cheap.”

“There was so much to carry from Tesco, I couldn’t add wine!”

“Should have thought ahead and bought a car instead of a house.”

“Meg.”

“Nobody will think you’re a twat,” I say. “They’re coming because they love you. And want to believe the rumours are true and new-build houses don’t have suspicious patches of damp.”

The doorbell rings. It’s not the head-splitting buzz that Poppy and I had in our old flat. I wonder if it’s you. My stomach dances at the thought.

“That’ll be Isobel,” Poppy says, turning towards the hallway. “I told her to come early so I could give her a tour of the house.”

“She asked for a tour of the house, didn’t she?”

“Yes.”

“Hang on,” I say, looking back around the table. “I’m the only one you haven’t paired up.”

“You’re with me. We haven’t done something together for ages.”

“I wouldn’t really call this doing something together.”

“I know. It’s just been mental. I still haven’t found a new assistant at work and buying a house is… exhausting.”

Exhausting, sure. But Poppy still had time to go to a 60th birthday party for Jack’s aunt last weekend. I saw on her Instagram. I didn’t double tap to like it. I screenshotted it and sent it to you.

“What about your boyfriend? You know, Jack? The one you’ve just committed to a twenty-five-year loan with?”

“Yeah, but he’s not you.”

You’re the last to arrive.

“Is that Jules?” Isobel whispers to me when you walk into the living room, kiss Poppy on the cheek, and push a pack of Peroni onto the kitchen counter. Isobel giggles behind her glass of Prosecco.

“That is Jules,” I affirm. I could tell her that your cheeks are as smooth as a fresh peach. That one of my favourite things to do is run the tip of my nose along your cheekbone while we’re watching Coronation Street.

“I’m really into that whole look now. My last girlfriend was much more like me. Like femme, you know? I think it’s something to do with getting older.”

“I’ve started to like mackerel as I’ve gotten older.”

Isobel gives me a withering look. I recognise it from Nicky Robinson’s reign of terror in high school. It makes me want to lock myself in the toilets and put my feet up on the door, so nobody knows I’m there. Nicky Robinson’s withering looks only stopped in year 10, because Poppy told her to stop calling me a dyke or she would show everyone the picture she’d taken of Nicky giving Harry Riley a blow job on the coach back from Beamish.

“Have you met her before?” Isobel asks, nodding discreetly towards you.

I met you at Poppy’s 29th birthday. Before we were introduced, Poppy whispered that you’re the only girl on Jack’s five-a-side football team. That was six months ago. Your hair was darker then; it gets lighter in the summer.

“Poppy said she’s really smart.”

“She is.”

Throughout the pear and fennel salad starter, Isobel keeps circling a finger around the rim of her wine glass, nodding sympathetically at your transport woes. You haven’t had an on-time train for five months.

“The other day, I needed to get from Leeds to Huddersfield and it was delayed by forty-five minutes. Then it was cancelled. I could have got the bus. This was at 8.30am so there was just me and this platform of mardy men huffing about renationalisation.”

I know all this. You keep a spreadsheet of your delayed trains. I don’t know what you’re going to do with it. Maybe it’s just proof that your annoyance exists, that we exist, that you get a train from my flat in Leeds to Huddersfield in the morning.

“Why were you in Leeds?” Jack asks.

“Just a meeting.”

“At 8.30am?”

“It was a breakfast meeting.”

“Those corporate donors must be riding you pretty hard if you’re finishing a meeting for 8.30am.”

“Thom,” I say, “what are the top three things you miss about dairy?”

He gives me a patronising smile. “Nothing, actually.”

“Not even pizza? I think I’d miss pizza the most. Pizza and yoghurt. Don’t you miss yoghurt? Do you have soya yoghurt instead?”

“First off, soya is unethical. And unsustainable.”

“Unsustainable?” Poppy says, pinching my thigh under the table. “How so?”

“So, come on, Jack,” Nisha calls down the table after he and Poppy have served the poached rhubarb dessert and put our plates in the dishwasher. “How much was the deposit?”

Poppy shakes her head. Talking about the pile of money which was waiting for her when her estranged father died makes Poppy feel grubby.

“Twenty-five grand,” Jack says. “We got the price down from two-sixty. Nightmare. Wasn’t it, Poppy?”

“You can get a place in Wakefield for half that.”

“Prices are insane around here. I’m shocked you even managed to get a place.”

“And as soon as anything with a garden and a parking space comes on the market it’s gone in seconds.”

“We must have looked at about twenty houses. These weird open houses with couples who looked exactly like us. Proper strange, wasn’t it, Poppy?”

“Uncanny.”

“That’s because you’re conforming,” I say. I nudge Poppy’s knee with mine, so she knows I’m joking. I’m sort-of joking.

Jack ignores me. “It’s like being stalked by yourself. We went out for a drink with one of the couples. Dead nice. He works in sustainability too, Thom. They’ve not managed to complete yet though. We’re meeting them next week for dinner.”

I think what profoundly irritates me about Jack is his complete confidence that he’s leading his life the right way because he sees other people, who look like him, doing exactly the same thing.

“What’s your interest rate?”

“Did you have a Help-To-Buy ISA, or a normal one?”

“And, be honest, Jack, did you have help from your parents like Poppy did?”

“We’ll all be dead from the climate emergency in ten years anyway, so what does it really matter?” I say. Poppy finds my hand under the table and squeezes it in thanks. Isobel smirks at you. I want to smash my plate over your head when you smile back.

I escape to Poppy’s second bedroom which she has forbidden the guests to go in. The rest of the house is well-ordered, but this room is filled with unpacked boxes of Poppy’s books and winter coats, and the bike Jack never rides leaning against the wall. I don’t want to go back downstairs. Jack is pounding on his guitar and the rest of the guests are singing along to ‘Wonderwall’.

“Are you starting a splinter group dinner party?” You ask from the doorway.

“Yes,” I say. “I’m the Chuka Umunna of dinner parties.”

You laugh. A proper laugh. The same way you laugh when your shirt sleeves are rolled up, you’re chopping vegetables, and I tell you about Wendy in HR’s thoughts on Tinder. I want you to close the door, put your hands on my wrists, and your mouth on my neck.

You look out onto the landing. There is nobody there, and I can’t hear anyone coming up the stairs. You shut the door. “When do you want to go?”

“Now,” I say, pressing the heels of my hands into my eyes. “I don’t know how much mortgage chat I can take.”

You look at your phone. “Fuck me, twenty minutes for an Uber.”

“It’s the suburbs. I’m surprised they even have Wi-Fi here.” I can hear you tapping at your phone. I pull my hands away from my eyes. “Were you flirting with Isobel?”

“Isobel’s a Tory, of course I wasn’t flirting with her.”

“You were very chatty.”

“What would you prefer me to do? Never speak to anyone until you want to tell Poppy we’re together?”

“So you were flirting?”

“This is silly.” You look up from your phone. “We hold hands. You’ve met my parents. We’re together. The only person who doesn’t know is Poppy.”

“I’m not telling her yet.”

You look pained. You put your phone back in your pocket. You hesitate. I know what you’re going to ask.

“Are you in love with her?”

“What?”

“I know I shouldn’t think that. I know that queer women can be friends with straight women without any sexual feelings coming into it. But… come on.”

There was one time that confused me for a while. We were 24, it was a Saturday night, and we had spent the day hunting through charity shops in Skipton. You bought a Charles and Diana memorial mug and I bought a slouchy lambswool cardigan that smelled of books. After we had our traditional Saturday night pizza and two bottles of red wine, we were propped up on pillows on Poppy’s bed. We were watching an episode of Gossip Girl and Poppy’s laptop was burning into my thighs. I could hear Poppy’s slow breathing and I knew she was about to fall asleep. At that moment, I felt so happy, so complete, and I thought: I will never meet anyone I love as much as you.

“Of course I’m not in love with her. She’s my best friend. She’s disgusting. She does horrible smelling shits with the bathroom door open when she’s hungover. I’ve watched her eat chips off the pavement for a bet.”

“You’ve told me that story before,” you say.

I lay back. In our old flat, Poppy had stuck glow-in-the-dark stars on the ceiling above her bed. We used to lay on it pretending to know about astrology. She would invent our future lives: my favourite was the one where we ran away to an old farmhouse in the Highlands. We would knit our own clothes, tend the vegetable garden and the chickens, and write our novels.

“If I tell Poppy then we’ll become Jules-and-Meg who hang out with Poppy-and-Jack. We’ll just be another one of their couple friends put on dinner party rotation.”

“She wouldn’t do that to you.” You sit down next to me and run your hand over my thigh. “I just think you should be honest with her.”

But I don’t want to be honest with her. When Poppy left our flat, our damp, magical flat in Headingley, to move in with Jack, she gave all the secret parts of herself, which had been for me and her, to him. And now I want to keep something of me from her. To spite her. To punish her for treating our friendship, our home and our life together, as a prelude to something more meaningful with Jack. She has never been my second-best. But she made me hers.

“She’d want to know how happy you are. You are happy, aren’t you?”

I sit up and kiss you. I run my hand over the bristles of your undercut. I love the feel of it under my fingers. I pull away and put my forehead to yours.

“Of course I’m happy.”

Voices are on the landing: Nisha and Poppy. You stand up. The door opens.

“I’ve been looking for you!” Poppy cries. The glass in her hand sways and white wine sloshes onto the carpet. “Isobel just cornered me to tell me how much mon-”

Poppy stops when she sees you.

“Hi Jules,” Poppy says. Normally, she’s too polite to look confused, but the white wine amplifies her voice and exaggerates her expressions. She is creeping towards the dramatic, flouncing Poppy who used to drink cider and chain-smoke outside pubs. “What are you doing here?”

“I was looking for the bathroom.”

“There’s one downstairs, next to the front door. Nisha’s in the upstairs one.”

You slide past her and close the door behind you. I hear you clatter down the stairs. Poppy hides her laugh behind her hands.

“I think she fancies you.”

“Best break it to Isobel. I hope she hasn’t picked out her wedding power suit.”

“Honestly, Jules was staring at you all the way through dinner.”

“Maybe there was something in my teeth.”

“Why are you even up here?” Poppy asks. She sits down on the bed next to me. “Tweeting about how much you hate this boujie house party?”

“Headache,” I say. “Oasis.”

“He doesn’t know any Carly Rae Jepsen, sorry.”

“I don’t understand how you can love someone who plays a guitar at house parties.”

“Well, firstly, it’s a dinner party.”

“You’re right. Guitars are more acceptable if there’s a sit-down element to the evening.”

“Come back downstairs.” Poppy nudges me. “I’ll have a secret cigarette with you in the garden.”

It’s cruel that Poppy treats our old habits as nostalgia. She used to fool me into thinking I had her back: the Poppy that drank a bottle of white wine on a Tuesday night, the Poppy who sent me urgent pictures from the Zara dressing room to help her decide what to buy, the Poppy who would buy two Diet Cokes and two Kinder Buenos on her way home from work. But she always returns to her new life with Jack, leaving me Poppy-less again.

“Given up.”

“Pussy. Since when?”

“Couple of months ago.”

Someone is coming upstairs. I know it’s you from the way you jump the last step and give the door two sturdy knocks. You have your denim jacket on, your backpack on your shoulders.

“Poppy, thanks for having me over. Dinner was great.” You lean down and kiss Poppy on the cheek. “I’ve gotta dash; got an early start tomorrow. Megan, do you want to jump in the Uber with me? I’ll be going past Dock Street, so…”

“You can stay here if you want,” Poppy says to me.

“That’s OK. I’ll come with you, Jules.”

“No, stay! We’ve already been calling this Meg’s room,” Poppy nudges my shoulder. “You can pick whatever colour you want for the walls.”

“Megan’s got her own room in her own flat,” you say. There’s the hint of impatience in your voice.

Poppy turns to you, running her tongue along her teeth, ready to take a bite.

“How do you know where Meg lives, Jules?”

You hesitate. I hesitate.

“I’ve been to Megan’s flat before.”

“Have you?” Poppy says. There’s schoolgirl mocking in her voice. I know you can hear it. I feel anger alight in my blood “Why?”

“We’re seeing each other,” I say, lightly. Poppy turns to me. The laughter falls out of her smile.

Your phone vibrates in your jeans pocket. “The Uber is here. I’ll wait for you downstairs, Megan.”

I get off the bed. Poppy stays where she is.

“Are you joking?”

“No.”

“Seeing Jules?”

“Yes.”

“Jack’s Jules?”

My Jules.

“Poppy, I have to go. My taxi’s here. We can talk about it tomorrow.”

“You can’t just leave after telling me that. How long have you been seeing each other?”

“A couple of months.”

“Months? What the fuck, Meg. Why didn’t you tell me?”

I have never wanted to hurt her before. But when her name falls into the graveyard of my WhatsApp, when she keeps missing the beat in our private jokes, when our trips to the pub, the cinema, to bottomless brunch always include Jack, when she talks about the holidays I’m not on, when she talks about the future that castrates me into her fucking guest bedroom, she is kindling a universe of hurt.

“Because I didn’t want to.”

We pull away from Poppy’s new house. You are looking out of the window. Poppy is standing on her front step, looking at me, neither smiling nor waving. I know she’s going to cry; her wobbling chin always betrays her.

“You were right to tell her,” you say. “She’ll get over it.”

“I know.” I’m watching Poppy. She doesn’t look away as we leave.

I know that when we’re out of sight, Poppy will walk upstairs, lock herself in the bathroom and cry into a towel. I used to be the one who sat outside the door, asking her if she was OK, if she wanted to talk about it. She would never answer, but I would always make her a cup of tea – milky with a heap of sugar – and leave it outside the door. I hope Jack knows to leave it there, and that she doesn’t mind if it goes cold before she unlocks the door.

Let Me Know When You’re Home: Stories of Female Friendship

In Let Me Know When You’re Home, fifteen women writers look at female friendship in all its forms, in a collection of fiction, non-fiction and poetry.